One of the juiciest stories in recent Silicon Valley history is currently unfolding. In case you haven’t heard: over the weekend, Sam Altman, co-founder and CEO of OpenAI, was fired by his board for reasons as yet unclear. Immediately following the announcement — made via OpenAI’s blog — the Internet (i.e. X) went, as you might expect, wild. After all, Sam — affectionately known as ‘Sama’ — is no ordinary founder / CEO. Rather, he has become the public face of the AI industry as a whole, and, as such, the veritable main character of planet Earth as of November 2023.

While the OpenAI announcement was light on details, the general thrust appeared to be that Sam had been intentionally deceiving the board in some fashion — ‘lacking in candour” was the corporate line. Sam had gone rogue, it seemed. And yet, not even 24 hours after the announcement, the OpenAI board appeared to be recanting, and was/is apparently in talks to hire him back (this after a whole cast of OpenAI staff had tendered their resignation in a touching show of solidarity with Sam). Thus what at first appeared to suggest some act of corporate malfeasance by Sam had begun to hint at something else. As of this moment, the consensus bet as to the source of this whole drama is an ideological schism, with AI safety folk on one side (Ilya and co), and accelerationists (Sama and friends), on the other. Putting aside for a moment whether this is in fact the case, this apparent schism reflects a broader — and very real — ideological divide within the industry (and society as a whole), as hopes and fears re the impact of AI reach fever pitch.

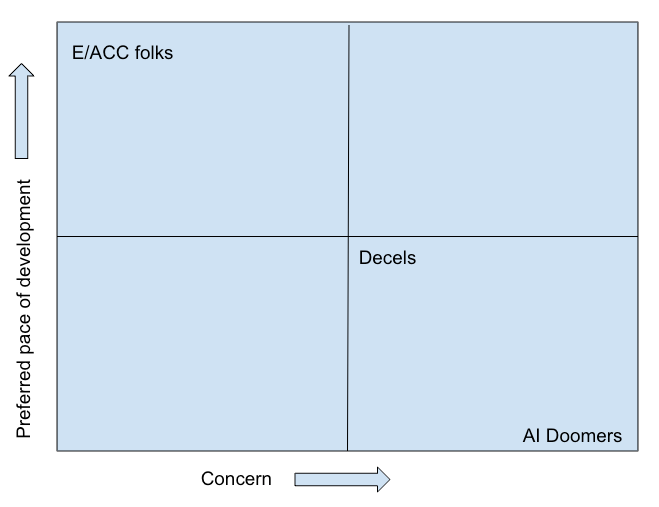

Fundamentally, this divide can be reduced to the following: some folk (so-called ‘decels’) think that AI — and AGI, specifically — represents a technology so *potentially* powerful that we ought to be conservative in our approach to its development, err on the side of caution, take our time with things. While today’s instantiation of AI is benign enough, a far more capable instantiation of AI — and certainly AGI proper — might conceivably dislocate the economy, further fracture our epistemic landscape, and, in the worst case, violently kill us all. On this view, naturally, the prudent thing to do is prioritise safety and alignment above capabilities. Conversely, the accelerationists believe that, given the inevitable positive impact of AI/AGI, we ought to do everything we can do develop capabilities as fast as we can, and simply figure out safety / alignment as we go. While there are plausible enough risks of AI, there already exists highly concrete, civilization-scale problems, from poverty to global warming, that can be solved with AI — if not today, tomorrow —and so we have a moral imperative to put our collective foot on the gas. Or so the accelerationist line goes. Of course, there exists nuanced, middle-ground positions that people straddle here, but broadly speaking these are the two buckets people tend to fall into. Either you’re pro-safety or pro-capability. Deceleration or acceleration.

When you consider this schism, OpenAI is a curious case. After all, it was founded on the premise of ensuring “artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity.” Although this seems like a reasonable enough mission, on its face, at the core of it lies a fundamental paradox; a paradox that almost certainly underpins the recent turmoil. You see, in order to ensure AGI benefits all of humanity, one must first build said AGI. For no matter how noble one’s intentions or sophisticated one’s imagined alignment plans, if someone else develops AGI first, it’s all for naught. At such point, the future is forever out of one’s hands.

Already we’ve seen this tension reflected in the evolution of OpenAI’s organisational structure. Infamously, what was originally a non-profit rather quickly became a very much for-profit (even if it’s capped). A cynic here would suggest that this flip simply represents the corruptibility of the human spirit, Sama and co’s lust for money and power. When it was all theoretic, they were a non-profit, but as soon as the potential for profit revealed itself OpenAI betrayed its original mission and decided to cash-in instead. However, a more charitable — and I would argue, equally reasonable — interpretation would be that this shift was actually implied by an earnest commitment to the mission. Developing AGI would obviously require immense resources, it was concluded, and in order to realise said resources, OpenAI realised it would need to employ the use of some explicit financial incentive. And so, valiant missionaries that they are, they did — and now the company is valued at ~$80B dollars and owns and controls the most powerful LLM and strongest AI talent going.

As a result of this organisational pivot, OpenAI has done more than any other organisation to accelerate the development and deployment of AI. While alignment alarmists and AI doomers spend their days waxing philosophical about the existential threat of AI, OpenAI ships products and raises billions to develop capabilities further. The contrast is stark.

Against this backdrop, it’s not hard to imagine that some subset of the company has grown uncomfortable with its direction. After all, if you’re at OpenAI and genuinely concerned about existential risk, it’s not unreasonable to feel a little conflicted about the day-to-day work of rapidly advancing capabilities. Even if you’re intent on summoning the demon, it’s one thing to slouch towards Bethlehem, quite another to sprint.

Irrespective of which side of the divide you find yourself on — decel or e/acc — it ought to be acknowledged that at the foundation of this whole ideological battle lies a fundamental uncertainty. That is, the outcome of AI. However disconcerting it is to admit, whether AI will be a boon to the human condition or the end of it entirely no-one knows. As of this moment, anyone’s guess is as good as the next. We can have intuitions, sure, even develop complex systems of logic and belief and, as good Beyesians, assign probabilities to the various outcomes on the basis thereof. However, the inconvenient fact remains that the future is fundamentally unknowable. Things might go good. Or they might not. It’s a flip of the coin.

As disturbing as this reality is, the situation is not unique to AI. Every day we take actions based on uncertain facts, and uncertain knowledge of the future. Without thinking, we get onto planes not knowing if they’ve been serviced. We drive our cars not knowing if we’ll be t-boned pulling out of our driveways. Perhaps most optimistically of all, we swear our lives to relationships that could end at any moment. The most remarkable fact of all this, however, is not that we play dice with our lives in the first place, but that we do so (for the most part) with so little existential angst. Any remotely well-adjusted human accepts the fundamental uncertainty of life and insists on playing anyhow. It’s simply how the game goes.

Where AI differs from the banalities of everyday uncertainty is of course in its normative significance. We’re not just talking about the fate of our own respective lives, small as they are. Instead, we’re talking about the fate of the entire moral sphere — the ‘light cone’ of all present and future value in the universe. Accordingly, the actions we take here shall ripple through eternity. This all to say, the stakes are rather high.

The question, then, provided the fundamental uncertainty and stakes at play, is what to do? Specifically, how should we relate to this technology, how should we orient towards its development, given we have no ultimate idea as to how it will unfold? If it really is a flip of the coin, and the whole world hangs in the balance, is it really justified to stay the course, to move forward knowing we may just be summoning a veritable demon? But what if AI is the precursor to a world of abundance in earnest, of heaven on Earth? The essential precondition to utopia.

It’s hard to conceive of any hard and fast rules here. However, one principle that seems sound enough, is to maintain and embody a bias towards empirical reality over abstract theoretical / probabilistic arguments. While there exists some cogent enough arguments for the existential risks of AGI, the on-the-ground Reality of things, presently, is that AI is conferring far more value upon society than it’s undermining or positively destroying. LLM’s, like ChatGPT, and image generation models, like Midjourney, are powerful augments to human capabilities. That is, they extend the reach of what any given human, or humans, can do. In this sense, AI is analogous to the personal computer itself — a technology which, however problematic, we’d hardly consider doing away with. Of course, this isn’t to suggest that AI, as it becomes (if it becomes) exponentially more powerful, won’t begin to flip from positive to negative. However, as a matter of practice, the only reliable feedback mechanism we have for informing our actions is Reality in-the-present. Indeed the present is the only firm epistemic ground we ever stand on. Therefore, the only prudent thing to do, it would seem, is base our actions on the way thing already are, not how they might be provided some series of conditionals. While speculations as to how things might be are worth considering, to be sure, we shouldn’t allow them to override the signal of empirical reality. On this point, there is a long list of speculations and arguments pertaining to far-off possibilities that have aged very poorly. Consider Ehrlich’s population bomb, for example. What Ehrlich underestimated, as so many doomers before him, is the reach of human ingenuity, the capacity of the human condition to rise to the challenges it invariably faces. Perhaps more fundamentally, though, Ehrlich’s prediction ought to remind us of the overhelming complexity of the world, and the utter unpredictability of non-linear, dynamical systems. Amidst this staggering complexity and unpredictability, the only tether to sanity we have is the present. As such, it pays not to get too far ahead of it.

Now even if you buy the existential risk argument(s), there remains the pragmatic fact that we will unquestionably continue to develop AI capabilities. If ever there was a certainty this is one. For every team that elects to halt development or even shut down shop entirely, there will be ten more that will pick up the slack. Moreover, it’s not clear at all that slowing development is actually consistent with improving our prospects of aligning it. Indeed it seems entirely reasonable to believe that they only effective way to align AI is to remain in constant dialogue with it, to build the safety rails as its evolving. After all, how could we possibly align a technology that doesn’t yet exist? Given the unpredictability of the world, we can never know in advance how things will precisely play out. We can only ever respond to them as they do. Turn off AI development and you turn off the very feedback mechanism by which we could optimise its safety. As such, the only way to effectively align AI is to swiftly respond to the challenges as they arise. To build the plane while we fly it. However daunting this task may seem, it is nevertheless, I suggest, the task we’ve been handed. To pretend like we have a choice is to engage in nothing but a flight of fancy.

However, if there was one thing that the recent OpenAI drama has highlighted, something that really should give us cause for concern, it’s just how fragile the present institutional structure that’s currently developing the technology is. Notwithstanding OpenAI’s apparent attempt to innovate at the level of its corporate structure, to ensure its aligned, clearly it is less robust than we would like; liable to disintegrate under the most modest of strains. What this would seem to suggest is that the highest leverage thing we can do to ensure the long-term alignment of AI/AGI is to see that the social containers in which it’s developed and deployed are themselves congruent with our broadest interests, capable of enduring the stress-tests that will inevitably arise. This should be cause for optimism. For while we have very little ultimate control over the advancement of the technology itself, improving the underlying organisational architecture that facilitates it seems — even if immensely challenging — relatively more tractable.