I’ve committed my career to working alongside early-stage startups. I got my first exposure to startups at Miami Angels, an early-stage angel investor syndicate, but eventually, it became obvious that being an employee (or founder) of an early-stage startup made much more sense for me than being an investor.

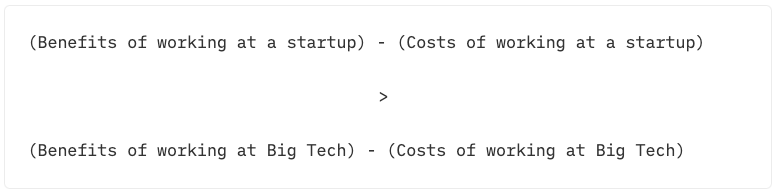

Here is a simple decision-making framework that I used to commit myself to startup life, and some words of encouragement for those of you considering doing the same.

First, the general premise:

-

Startups will require a ton of challenging work to be successful.

-

Startups will have minimal infrastructure in place, at least in the early days (e.g., no HR department for recruiting, no Finance team for managing reimbursements)

-

Startup employees take lower salaries in exchange for higher upside.

-

Startup employees own a portion of the company, and the fundamental bet is that the startup will be worth much more in the future.

I’ll refer to the ‘other option’ here as Big Tech, although any other industry could be retrofitted into this framework (like biotech startups vs. Big Pharma, or consumer startups vs. the big consumer brands).

-

In Big Tech, you’ll have higher salaries, more perks, and job security.

-

In Big Tech, you’ll have less stress, pressure, and responsibility.

-

In Big Tech, you won’t have to do much context-switching — you’ll be able to focus just on your work, since other parts of the organization will already be built out to support your work.

I don’t think the premise is necessarily true for all of the points above. In fact, I think several of these points are outdated or misrepresented. But let’s consider these the foundational arguments for each side of the table.

From here, we’ll outline a simple equation for measuring the trade-offs.

On one side of this equation, we have the costs and benefits of startup life.

On the other side, we have the costs and benefits of Big Tech life.

On the startup side of the equation, you’re joining for the equity that you’ll own in the business. What could that equity be worth in a positive scenario, and how likely is it to reach a point where you can actually turn that equity into cash?

Some questions you could reasonably ask yourself:

-

What is the likelihood of success for this startup? (Very difficult to quantify!)

-

What valuation would the startup have to reach for me to consider it successful?

-

How much more money will this company need to raise in the future, and how does that impact my ownership?

-

How much do I own of the company in this hypothetical?

-

How much am I getting paid while we build the company?

With these answers in hand, we could imagine doing the math to get to an expected value of working at a startup. Multiply your ownership in a startup by the probability of the company’s success, then multiply that by the valuation of the company in a successful outcome, and poof! You get a reasonable expected value of your equity at a startup.

But there’s a metric fuckton of uncertainty here — the macroeconomic climate at any point in the future, the probabilities of success, and even the task of guessing what a company might be worth in the future. Being too specific with these numbers can make us feel deceivingly certain about something that should have no degree of certainty whatsoever.

The idea here is not to be overly precise, given this uncertainty, but instead to develop a mental model for evaluating the potential costs and benefits of joining a startup versus working in a traditional, large enterprise. We are refining a mental model by thinking through the various inputs into the above formula.

This has been strictly financial so far, but one of the main tipping points for my own calculus is that I believe the abstract value in working for a startup matters, and it matters a lot.

Being incentivized in the day-to-day work — actually feeling like your work is driving value in the business! — makes work much more fulfilling, and ideally, the startup you are joining has been targeted (by you) to align with your belief system, so that you can feel satisfied working towards the startup’s mission.

The opportunity to ‘wear different hats’ every day in a startup — to deal with uncertainty, tackle miscellaneous challenges, work your brain muscles day-in and day-out — is a useful practice for developing actual tangible skills. These skills are useful in almost any role outside of Startup Land, and the benefit of finding comfort in the uncertainty and actually getting good at these skills is highly underrated.

In fact, having less stress, pressure, and responsibility is a bad thing! It’s healthy to encounter stress, pressure, and responsibility on a semi-frequent basis. I personally want to expose myself to challenging situations, think through creative solutions, and strive to compete against others. Seeking out less responsibility is just not in my DNA.

A short digression here — I feel that a Matrix-like curtain has been forced over our eyes to make us think that work is supposed to be empty and dry. The Mondays through Fridays slowly passing us by, the boredom of a draining professional career sucking life out of us until we look up at 80 years old and wonder where the days have gone.

This does not have to be the way we live. You can choose the red pill and escape the rat race of middle management. You can rid yourself of Sunday scaries, replacing the anxiety of another long boring week with the supercharged motivation to go out and drive actual value to the company you work for and own a small piece of.

We can live fulfilling personal and professional lives; it doesn’t have to be either-or.

So these are the benefits of working at a startup. There are also costs.

The costs of working at a startup include: the inherent riskiness of startup life, the huge pay cuts that you need to take to join a startup, and also, what happens if the economy crashes?!

I firmly believe that each of these points is outdated or misinformed.

On layoffs — Big Tech (and large enterprises overall) have been ravaged by layoffs over the last few years. People who thought they had job security were suddenly called into meetings with faceless HR representatives to hear that ‘the company is going another direction,’ a wake-up call for those that assumed that working at a big company meant you could effectively hide in the crowd of 100,000 employees.

And many startup salaries no longer require a life of living in a garage and eating a Ramen diet. There’s more money in the startup ecosystem, and startups have come around to the idea that hiring and retaining employees will require more than just the allure of company equity. Even perks like health insurance, 401(k)’s, corporate credit cards, and disability insurance are easily accessible to most startups today, simply by using the crop of other startups that have been built over the past decade to enable this — companies like Deel and Mercury and Sequoia One.

With respect to the economy, I’ll simply quote from a Paul Graham post from 2008:

October 2008

The economic situation is apparently so grim that some experts fear we may be in for a stretch as bad as the mid seventies.

When Microsoft and Apple were founded.

As those examples suggest, a recession may not be such a bad time to start a startup. I'm not claiming it's a particularly good time either. The truth is more boring: the state of the economy doesn't matter much either way.

(A small but meaningful side note — Within just 12 months of this PG blog post, in the midst of the deepest recession since the 1920’s, Paul Graham and Y Combinator invested in Stripe, Airbnb, PagerDuty, and Heroku, which cumulatively account for somewhere around $200 billion dollars of equity value today.)

So to recap:

In this framework, you try to guesstimate what your equity might be worth in a successful outcome, discounted by some large percentage to account for probability of failure, and you add back in all of the abstract benefits — the feeling of having ‘skin in the game’, working on a mission you believe in, and the genuine development of useful, varied problem-solving skills.

Then you subtract out your own perception of startup costs; the presumed riskiness, the less frilly benefits, any macroeconomic concerns that you might hold.

My core argument is that the explicit benefits of working at a startup are clear. In the small chance that the company succeeds, you’ll probably get very rich, but it’s the implicit, often-under discussed benefits of working at a startup that are underrated in this calculation.

And the costs of working at a startup — the instability, the low salaries, the Ramen diets — are vastly overrated in today’s startup culture, given the amount of capital and brainpower that has been redirected towards startups over the last few decades.

Meanwhile, the benefits of Big Tech are also clear. High salaries, good perks, and good work-life balance are alluring. But how large is the cost of being one small cog in a 100,000 employee machine? How draining is it to work without caring about the company mission, and without being able to see any of your work drive tangible value for the business?

Ultimately, this framework relies on deciding which side of the equation is worth more to you. I’ll leave it to the reader to do the Big Tech side of the calculation for themselves. Of course, the specifics matter here, but readers can impart their own judgements and their own situations into the calculus.

For me, the math is clear. I’ll bet on myself.

I’ll bet on my ability to act as venture capitalist with my own salary, time, and effort, by picking the right companies to work on, and I’ll bet on my ability to influence meaningful change at the companies that I join to help us get a little bit closer to that desired successful outcome.

To be clear, this is a gamble — one big, concentrated bet into the companies I join — but it’s different from betting on a sporting event or a roulette spin. This is a gamble I can reasonably influence by contributing meaningful, high-quality work to the company. It’s a gamble, but with my time, money, effort, career, and life.

I’m okay with the stakes; the stakes empower me to be the best version of myself in my day-to-day.

If you’re considering a switch into startups, let me leave you with some words of advice and encouragement.

-

Do the hard work of deeply introspecting and reflecting on what kind of work you want to do for the next decade of your life. Use this exercise as your guiding light when searching for startups.

-

Spend time learning about the startup landscape in the industry of your choosing. You could join the biggest, ‘least-startup’ startup in that industry — OpenAI, for example — or you could join the 2-person team coming at the titans of industry. Even amongst startups there are huge variations in team size, type of work you’d be doing, and the upside you can expect to get, so think deeply about what your risk tolerance is and what kind of work you want to be doing.

-

Follow startup funding announcements! Daily newsletters like StrictlyVC or Axios Pro Rata are good for this. As a general rule, companies that have just fundraised will be the most likely to be hiring in the immediate term, but don’t confuse these funding announcements for success. Venture funding predates success — the work is still ahead for venture backed companies.

-

It's important to acknowledge that both the startup landscape and the BigTradCompany landscape have thousands of different companies, each with varying levels of risk, reward, and work-life balance. It’s okay to decide that you value Big Tech life more than startup life! Just make sure you’re making that decision after careful consideration, rather than just because of typical life inertia.

-

Read all of Paul Graham’s startup blog posts, like:

If you’re considering joining a startup and want to talk through it, DM me on Twitter. I’d be happy to help you think through it. And if you’ve enjoyed reading this, I encourage you to subscribe to my Mirror profile to get an e-mail every ~6 months when I write a new post.