Introducing core DAO leadership [long read]

tl;dr

- Distributed organizing makes research on DAO leadership a priority

- DAOs can benefit from succinct roll-ups of what research has taught us about leadership over decades

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are highly efficient ways to examine large bodies of research and derive implications for practice

- This essay contains the juice of leadership research to ground future research on DAO leadership upon a solid foundation

- DAO leadership involves self, people, task, and change leadership behaviors that members share responsibility to perform to drive DAO outcomes

Contents

- What can DAOs learn from decades of leadership research?

- Building on «research of research»

- Preliminary perspective on DAO leadership

- Leadership and DAOs

- Working definition of DAO leadership

- Introducing core DAO leadership

- DAO leadership is shared

- What are the conditions for shared leadership to emerge?

- What is «shared» in leadership?

- Leadership behaviors that drive outcomes

- On leading

- Leaders are made, not born

- Are you motivated to lead?

- No noise, just signals

- Leading self

- Self-leadership

- Leading people

- Transformational leadership

- Empowering leadership

- Servant leadership

- Leading tasks

- Initiating structure

- Transactional leadership

- Boundary spanning

- Laissez-faire leadership

- Leading change

- Charismatic leadership

- Instrumental leadership

- Intellectual stimulation

- Wrapping up: core DAO leadership

- DAO Leadership NFT Editions

- Acknowledgements

- Disclaimer

- About us

- References

1. What can DAOs learn from decades of leadership research?

Building on «research of research»

At talentDAO we set out to study leadership in the decentralized world of work. We are building our point of view on high-quality, high-applicability leadership research. Our research protocol consists of:

- Step 1: Build on «research of research» conducting rapid reviews of meta-analysis or systematic reviews to leverage the best scientific research on leadership

- Step 2: Consolidate, summarize, and share existing leadership research and potential DAO implications

- Step 3: Conduct primary quali-quantitative research within DAOs informed by our prior research, hence «building on the shoulders of giants»

This essay is the output of step 1 and 2. We reviewed 40 studies that used meta-analytic or systematic review methods, conducted over the last 25 years. These studies pool together quantitative results on specific research questions using the whole body of scientific evidence to date. Hence, the 40 studies represent around 5400 primary leadership studies with a total sample size of hundreds of thousands of leaders across a wide range of organizational settings. Given the characteristics of this evidence base, we expect the findings to generalize to different contexts, including decentralized autonomous organizations.

You can find more details about our research project here.

2. Preliminary perspective on DAO leadership

Leadership and DAOs

Leadership enables organizations to function effectively, directing, inspiring, and coordinating the efforts of individuals, teams, and organizations toward the realization of collective goals (Carter, 2015). Leadership research started getting attention after World War II. Over the past 70 years the field has grown exponentially through multiple «waves» of research: from simple behavioral theories, to more sophisticated cognitive explanations, to the emergence of leadership in complex, dynamic networks (Lord, 2017).

Leadership is conceptualized as a «dyadic, shared, relational, strategic, global, and a complex social dynamic» (Avolio, 2009). In one-word leadership means influence. Leadership synonyms are power, authority, decision-making.

DAO stands for decentralized autonomous organization. We defined a DAO as a blockchain-enabled organization with shared community, purpose, and capital.

For many people talking about leadership in DAOs is an oxymoron. In fact, claims about DAO leadership abound: they are leaderless, there are no bosses, software rules aka «code is law». Yet how can DAOs coordinate without leadership? What if everyone is a leader instead?

https://twitter.com/JulzRoze/status/1454114301128626176?s=20&t=UHmbFRrlybqMSSXcyWsOLQ

Working definition of DAO leadership

The rise of decentralized organizational designs and self-managing teams calls for new inquiry into what constitutes leadership. Given the decentralized nature of DAOs, we have been looking for more appropriate forms of group leadership than hierarchical leadership. We noticed the leadership field is moving from a leader-centric and individual-level phenomenon, to a dynamic and interactive group-emergent property, as captured by research on shared, distributed, and collective leadership in the realm of network science (e.g., Carter et al. 2015; Contractor et al. 2012; Scott-Young et al. 2019). As such, we provisionally define DAO leadership as:

a dynamic, emergent group property in which people flexibly lead one another - selectively using skills and expertise based on the evolving needs and context of the DAO - by sharing responsibility to perform specific leadership behaviors to achieve group or organizational goals

At a deeper level, let’s distinguish what DAO leadership is, and what it is not:

- Leadership is relational, versus top-down influence from one to another. DAO leadership is interactive. Without followers there are no leaders, and without leaders there are no followers. In DAOs, when one person engages in leading, the other accepts the following and vice versa. Put simply, «no one should lead all the time and everyone should lead some of the time» (credits Enspiral).

- Leadership is a process or action, versus a status or title. DAO leadership is a role function or set of behaviors anyone can perform depending on the demands of a situation. Based on the function you can serve or the problems you can solve, in DAOs you are «a» leader, not «the» leader (credits @tracheopteryx).

- Leadership is heterarchical, versus hierarchical. DAO leadership is heterarchy with flexible hierarchies. In theory, heterarchy means everyone has the same degree of power or authority. Yet leading accrues power to individuals; thus rotating authority overtime through flexible hierarchies helps to adjust power asymmetries that arise, in terms of information, relationships, skills, reputation, money and time (credits Enspiral).

DAO leadership is shared

DAOs are neither horizontal by default nor are hierarchical by destiny. We assert that core DAO leadership is shared rather than centralized in the hands of a single person. When we form a shared leadership culture in a team, members co-govern, participate in decision-making, undertake their tasks collectively, and occasionally offer guidance to other team members to achieve their common goals. Leaders emerge formally or informally based on the needs of a situation, so there is no one leader but multiple ones. Research on forms of collective leadership shows that shared leadership correlates with team performance, team viability (i.e., how much a team stick together), and team attitudinal outcomes, behavioral processes and emergent team states (D’Innocenzo, 2016; Wu, 2018; Wang 2014; Nicolaides, 2014); in particular, shared team leadership is a stronger predictor of team outcomes compared to hierarchical leadership in teams that are more virtual in nature (Hoch, 2014; Greer, 2018).

What are the conditions for shared leadership to emerge?

Our research points to three pre-conditions for shared leadership to emerge: shared purpose, social support, and voice (Wu, 2020). These factors require you to set up structural supports to ensure the group know where to go and how to get there (shared purpose), lend a hand to each other (social support), and can influence team direction and actions (voice). When shared purpose, social support, and voice exist in groups, teams are more likely to provide leadership and to respond to the leadership of others. When people share a common purpose, they are more committed to their work and more motivated to participate in leadership activities. Social support instead creates an environment where group members can collaborate better and feel responsible for results. Finally, when group members are willing to speak up and get involved, they are more likely to exercise leadership.

What is «shared» in leadership?

So far we discussed shared, distributed, collective leadership as the underlying framework of DAO leadership. We also outlined the necessary conditions for these forms of leadership to emerge, namely, shared purpose, social support and voice. What we are left to answer though is what is the content of leadership? What is actually shared in DAO leadership?

Leadership behaviors that drive outcomes

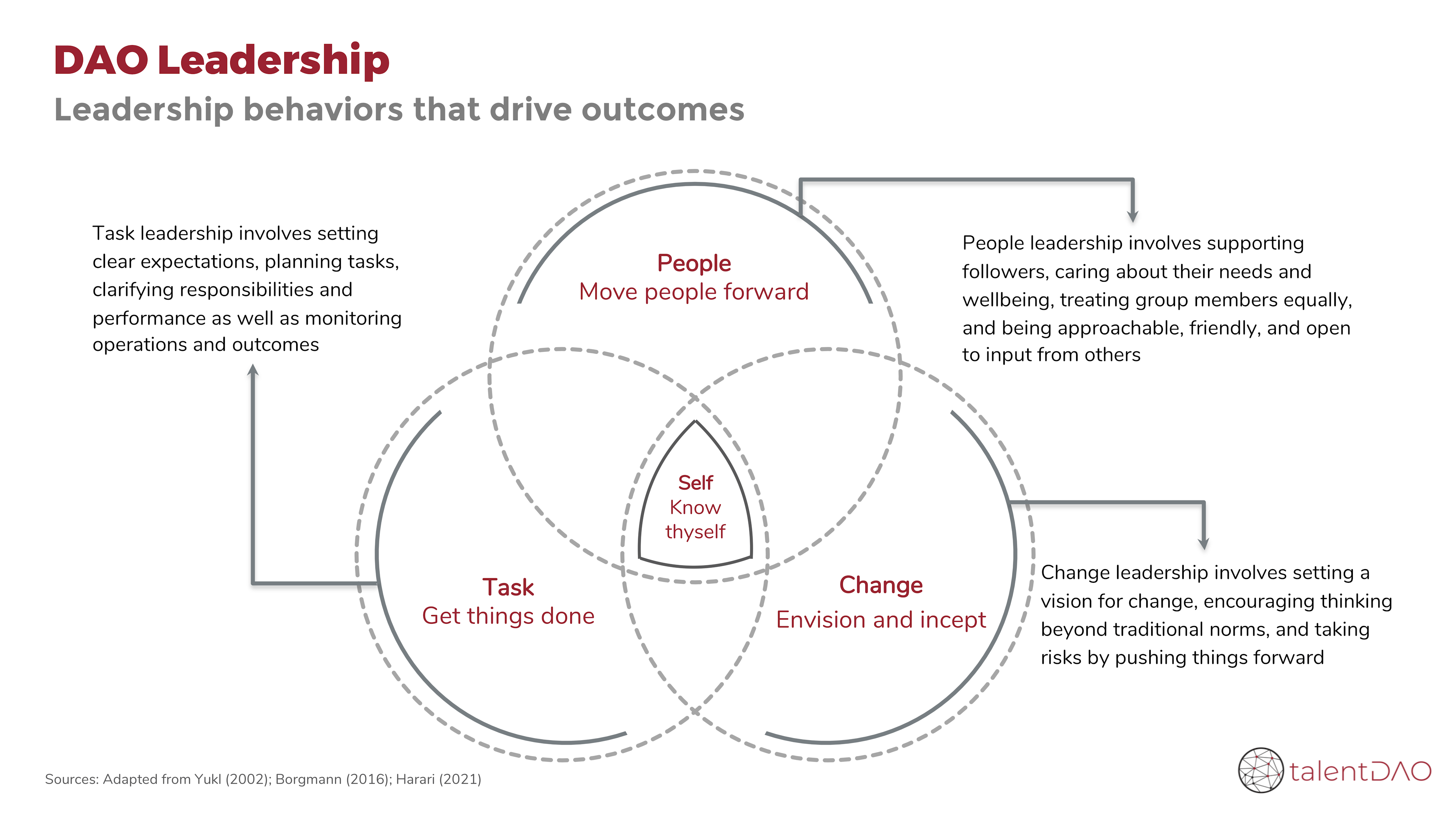

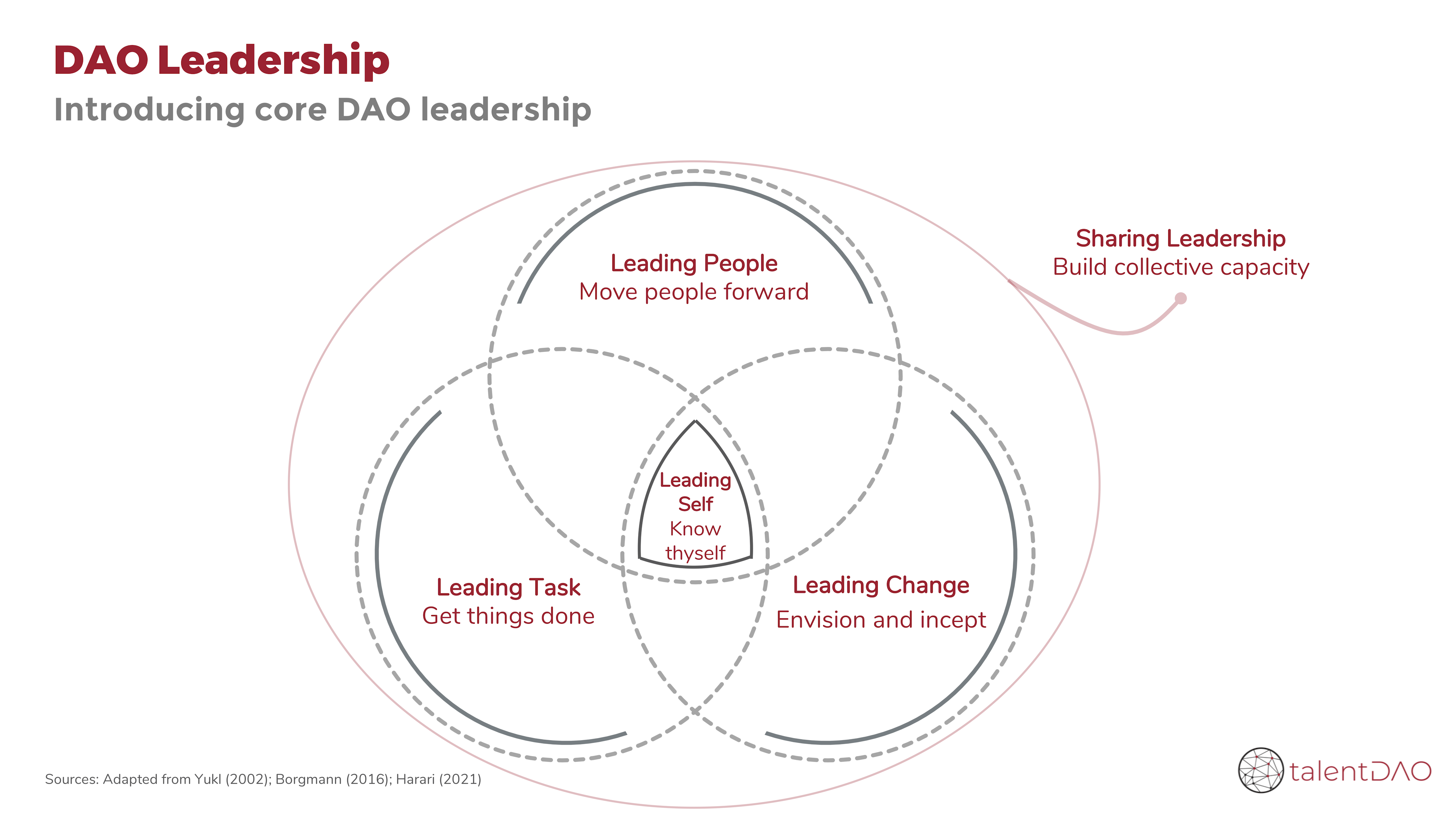

There are four categories of leadership behaviors that predict individual and organizational outcomes: people, task, change, and self-leadership (adapted from Yukl, 2002). To determine what is shared in DAO leadership we use this simple yet meaningful conceptualization:

- Self-leadership involves exerting self-influence over one's thoughts, feelings, and behaviors at work.

- People leadership involves supporting others, caring about their needs and wellbeing, treating group members equally, and being approachable, friendly, and open to input from others.

- Task leadership involves setting clear expectations, planning tasks, clarifying responsibilities and performance as well as monitoring operations and outcomes.

- Change leadership involves setting a vision for change, making strategic and tactical decisions, encouraging thinking beyond traditional norms, and taking risks by pushing things forward.

Researchers used this taxonomy to cluster multiple leadership models under each category and test their predictivity over outcomes. Our research shows that:

- Self-leadership behaviors correlate with individual performance, creativity, and self-efficacy (Knotts, 2021), individual productive thoughts, behaviors and attitudes (Harari, 2021), and development of self-leadership capacity (Krampitz, 2021)

- People leadership behaviors correlate with followers’ organizational commitment, task performance (Borgmann, 2016), virtual team performance (Brown, 2021), perceived team effectiveness (Burke, 2006), team learning behaviors (Burke, 2006; Koeslag-Kreunen, 2018), and followers’ fairness perceptions (Karam, 2019)

- Task leadership behaviors correlate with followers’ organizational commitment, task performance (Borgmann, 2016), virtual team performance (Brown, 2021), team productivity (Burke, 2006), team learning behaviors (Burke, 2006; Koeslag-Kreunen, 2018), and followers’ fairness perceptions (Karam, 2019)

- Change leadership behaviors correlate with followers’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment (Borgmann, 2016), and fairness perceptions (Karam, 2019)

4. On leading

Leaders are made, not born

Before diving into the framework, we need to correct a common misconception: people were born with a natural gift for leadership. This fixed mindset of you either are or are not a leader is as false as it is counterproductive. DeRue (2011) investigated whether innate characteristics like personality traits (conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, openness to experience, emotional stability) and intelligence were more important than behaviors in predicting individual leader outcomes. The conclusion is that what you do matters more than who you are, that is, leadership behaviors predict outcomes like leader effectiveness, group performance, follower job satisfaction, and satisfaction with leaders, more than leader traits do. Of course genes impact where the journey begins and may explain the speed with which you pick up leadership skills, however genetics doesn’t determine the destination. In fact, progress comes from luck and a whole lot of practice.

Are you motivated to lead?

One of the prerequisites for leading is to be motivated to lead. According to Chan and Drasgow (2001) there are three types of motivation to lead:

- the degree to which you enjoy leadership roles and see yourself leading

- the degree to which you view leadership as a responsibility and duty

- the degree to which you view leadership opportunities positively despite potential costs and/or minimal personal benefits

Those who have more motivation to lead are more likely to emerge as leaders, engage in beneficial leadership behaviors, and perform more effectively in leadership roles (Badura, 2020). Given the emergent nature of leadership in DAOs, the first question to ask is: Do I want to put my skin in the game?

No noise, just signals

Many leadership models exist today. Since «all models are wrong, but some are useful» (Box, 1976), we sought to separate the wheat from the chaff. We built our framework for DAO leadership to include only leadership models that predict individual and organizational outcomes across many organizational contexts. We have left out those models that, despite looking sound at face value, did not add anything to the more established frameworks.

In the next sections, we define leadership behaviors within the people, task, change, and self-leadership categories, outline what they are made of, and list the main outcomes they correlate with.

5. Leading self

Self-leadership

Self-leadership means leading from the inside out: you influence yourself through your own thoughts and behaviors before even thinking of influencing and leading others.

Manz (1986) defined self-leadership as:

a comprehensive self-influence perspective that concerns leading oneself toward performance of naturally motivating tasks as well as managing oneself to do work that must be done, but is not naturally motivating

At the heart of self-leadership there is your choice of higher-level objectives you want to achieve and the actions you take to regulate or control tactical behaviors to support such objectives. Research points to using two sets of strategies to lead yourself effectively: behavioral and cognitive strategies (Harari, 2021; Knotts, 2021; Krampitz, 2021).

Behavioral strategies

Behavioral strategies involve self-observation, goal setting, reward, and cueing.

- Self-observation aims to draw attention to the way in which you speak, think and act.

- Self-set goals follow observation as a way to change your behavior. With newly-gained awareness of your current behaviors you start formulating long-term, workable goals to reshape and refocus your own behaviors over time.

- Self-rewards can be small, such as rewarding yourself by giving yourself a pat on the back for accomplishing a small task; or bigger, such as taking your family out to dinner for successfully launching a new project.

- Self-cueing includes setting reminders like sticky notes or to-do lists and avoiding distractions like reading every Discord notification from that crazy DAO you just joined.

Cognitive strategies

Cognitive strategies include natural rewards, using mental imagery, developing effective self-talk, and challenging beliefs and assumptions.

- Natural reward means focusing on aspects of a task or activities that make it fun, essentially, turning tasks into games.

- Constructive mental visualizations involve thinking about yourself succeeding in a task before you actually do it.

- Self-talk refers to the things you say out loud in your mind, focusing on identifying irrational or pessimistic talks to replace them with more constructive inner dialogues.

- Identifying and eliminating dysfunctional beliefs or assumptions. There are three such beliefs or assumptions: «all-or-nothing thinking» in which you view even small imperfections as complete failure; «mental filter» which involves letting negative things through and not letting positive things through; «disqualifying the positive» where negative results are used to dismiss positive ones as flukes or just lucky.

Self-leadership outcomes

Our research shows that applying a mix of behavioral and cognitive self-leadership strategies correlates with:

- individual outcomes like performance, creativity, and self-efficacy (Knotts et al. 2021)

- individual productive thoughts, behaviors and attitudes (Harari et al. 2021)

- and interventions to increase people's self-leadership capacity are effective (Krampitz et al. 2021)

6. Leading people

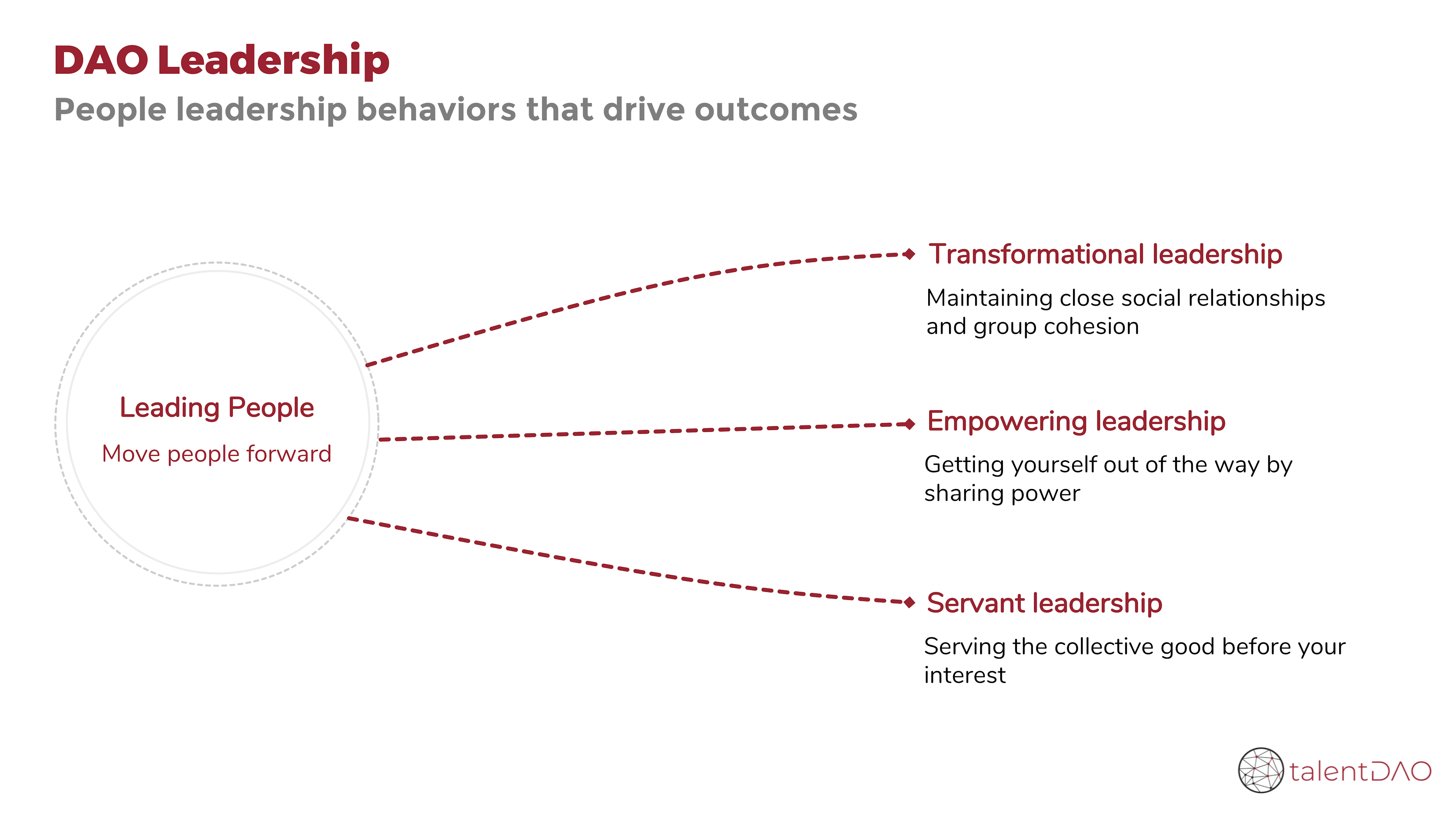

Leading people means giving attention to people before tasks. Leaders challenge team members to put the interests of the team ahead of their personal interest, encourage them to do more than they get money for, and support them to feel comfortable working autonomously. People leadership behaviors include transformational leadership, empowering leadership, and servant leadership.

Transformational leadership

Bass & Avolio (1994) defined transformational leadership as:

helping team members to move beyond their self-interest by challenging them and by stimulating creativity in their efforts to solve problems

Transformational leadership involves four sets of behaviors: individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, inspirational motivation, and idealized influence. While the first fall within people leadership, the last three behaviors better suit change leadership behaviors that we will discuss later.

Individualized consideration

Judge & Piccolo (2004) defined individualized consideration as:

the degree to which the leader attends to each follower’s needs, acts as a mentor or coach to the follower, and listens to the follower’s concerns and needs

The goal here is to maintain close social relationships and group cohesion using two-way open communication to build mutual respect and trust. Borrowing from DeRue (2011), giving people individualized consideration boils down to:

- Finding time to listen to group members.

- Treating team members as equals.

- Looking out for the personal welfare of each individual.

- Consulting the group and seeking input when making decisions.

- Getting group approval in important matters before going ahead.

Transformational leadership outcomes

Our research shows that transformational leadership behaviors correlate with:

- leader effectiveness, follower job satisfaction, satisfaction with leader, follower motivation, trust in the leader (DeRue et al. 2011; Judge & Piccolo, 2004; Nohe et al. 2017)

- followers’ task and extra-role performance (Ng, 2017; Wang et al. 2011) and creative and innovative performance (Hughes et al. 2018)

- followers’ identification with the leader and subsequent identification with the team and organization (Horstmaier et al. 2017; Koh et al. 2019);

- followers’ commitment to the organization (Jackson, 2013; Nohe et al. 2017);

- followers' fairness perceptions (Karam et al. 2019);

- lower followers’ stress and burnout (Harms et al. 2017);

- followers’ motivation for creativity, innovation climate, psychological empowerment (Koh et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2019)

- followers’ readiness, openness, and commitment to change (Peng et al. 2021)

- team/unit task performance, team/unit extra-role performance, team learning behavior, organizational-level innovative behavior (DeRue et al. 2011; Judge & Piccolo, 2004; Koeslag-Kreunen et al. 2018; Ng, 2017)

Empowering leadership

Sharma & Kirkman (2015) defined empowering leadership as:

leader behaviors directed at individuals or entire teams consisting of delegating authority to people, promoting their self-directed and autonomous decision making, coaching, sharing information, and asking for input

Empowering leadership means getting yourself out of the way by sharing power. If you have status and authority in your organization, empowerment translates into distributing decision making or leadership authority, encouraging others to express opinions and ideas, and supporting information sharing and teamwork. More specifically, empowering leadership behaviors include:

- Promoting and influencing the use of structures, policies, and practices supporting people empowerment by leveling asymmetries (of power, information, relationships, knowledge, etc.).

- Ensuring people have the authority to make their own decisions, rather than simply letting them influence yours.

- Encouraging others to set their own goals and enhancing their sense of confidence and personal control in their work through coaching.

Empowering leadership outcomes

Our research shows that empowering leadership behaviors correlate with:

- individual and team-level task and extra-role performance, creativity and innovation, team productivity, team empowerment, and team learning (Lee et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2018; Burke et al. 2006; Hughes et al. 2018)

- others’ evaluation of leaders like trust in the leader, quality of leader-follower relationship, perceived leader effectiveness (Kim et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2017)

- followers’ self-leadership, psychological empowerment, and role clarity (Kim et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2017)

- followers’ satisfaction, commitment, engagement, and knowledge sharing (Kim et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2017)

- lower followers’ emotional exhaustion, tension, and cynicism (i.e., burnout) (Kim et al. 2018)

Servant leadership

Eva et al. (2019) defined servant leadership as:

an other-oriented approach to leadership, manifested through one-on-one prioritizing of follower individual needs and interests, and outward reorienting of their concern for self towards concern for other within the organization and the larger community

Spears (2010) advanced 10 characteristics of servant leaders, including listening, empathy, healing, awareness, persuasion, conceptualization, foresight, stewardship, commitment to the growth of others, and building community. While servant leadership overlaps with transformational or charismatic leadership, it’s conceptually distinct as it adds moral behaviors:

- Doing what is right.

- Providing an appropriate model.

- Giving a positive example for others to follow.

- Leading by doing rather than telling.

Servant leadership outcomes

Our research shows that servant leadership behaviors correlate with:

- followers’ extra-role performance, engagement, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, trust in the leader, quality of leader-follower relationship (Hoch et al. 2016), team-level extra role performance (Lee et al. 2019)

7. Leading tasks

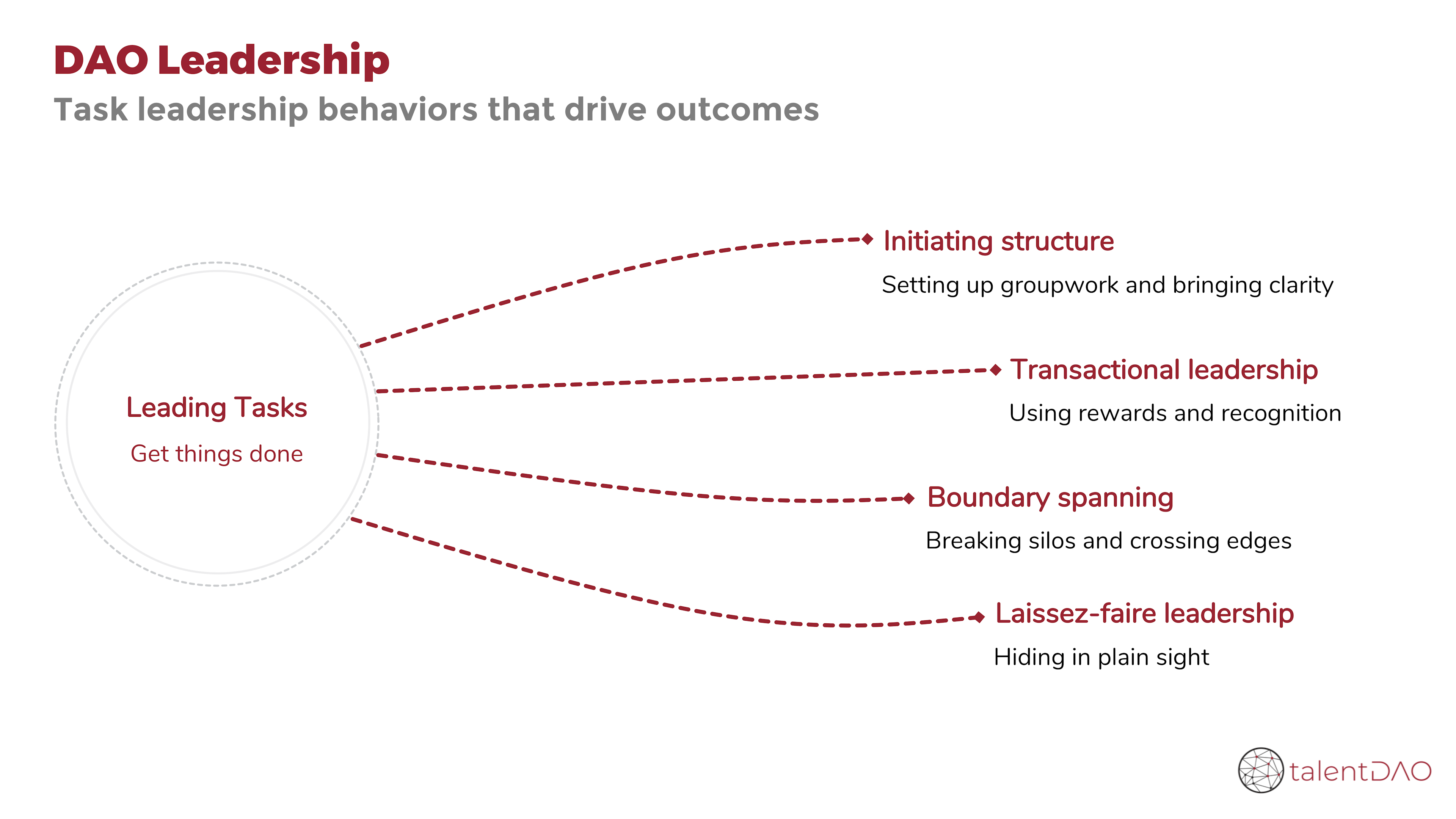

Leading tasks means doing what it takes to get the job done, such as determining goals and expectations, clarifying roles, creating plans, monitoring the team's progress over outcomes, and sharing rewards and recognition for achievements. Task leadership behaviors include initiating structure, transactional leadership, boundary spanning, and laissez-faire leadership.

Initiating structure

Burke (2006) defined initiating structure as:

emphasizing the accomplishment of task objectives by minimizing role ambiguity and conflict

Here leaders work to clarify a sense of direction and purpose for the group using two means:

- Directive behaviors: Starting and organizing work, assigning tasks, specifying how to get stuff done, putting emphasis on getting things done, and creating clear communication channels.

- Autocratic behaviors: Making decisions without getting input from team members.

Initiating structure outcomes

Our research shows that initiating structure behaviors correlate with:

- leader effectiveness, quality indicators of followers’ performance, perceived team effectiveness, team/group productivity, team learning (Burke et al. 2006; DeRue et al. 2011; Koeslag-Kreunen et al. 2018)

Transactional leadership

Burns (1978) defined transactional leadership as:

involving dyadic exchanges in which the leader provides praise, rewards, or withholds punishment from another person who complies with expectations

Transactional leadership is made of three dimensions:

- Contingent reward: Leaders recognize and reward others for their work and accomplishments.

- Active aversive influence: Active leaders pay attention to who is acting out of line and address the problem before it causes serious damage.

- Passive aversive influence: Passive leaders delay acting until they observe that the behavior has created problems.

Transactional leadership outcomes

Our research shows that transactional leadership behaviors correlate with:

- quality indicators of followers’ performance, perceived team effectiveness, team/group productivity, team learning (Burke et al. 2006; DeRue et al. 2011; Koeslag-Kreunen et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2011)

- followers’ job satisfaction, satisfaction with the leader, motivation, leader’s job performance, leader effectiveness (Judge & Piccolo, 2004; DeRue et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2011)

Boundary spanning

Brown and Eisenhardt (1995) defined boundary spanning as:

politically oriented communication that increases the resources available to the team and networking communication which expands the amount and variety of information that is available to the team

Boundary spanners work with others outside the team, scan the environment, and negotiate resources for the team, acquiring information to maintain situational awareness and facilitate effective problem solving. Behaviors may include:

- Investigating what competing groups are doing on similar projects.

- Collecting technical information/ideas from people outside the team.

- Finding out whether others in the organization support or oppose one’s team activities.

- Acquiring resources (e.g., money, new members, equipment) for the team.

- Coordinating activities with external groups.

Boundary spanning outcomes

Our research shows that boundary spanning behaviors correlate with:

- quality indicators of followers’ performance, perceived team effectiveness (Burke et al. 2006)

Laissez-faire leadership

Judge and Piccolo (2004) defined laissez-faire leaders as:

characterized by avoiding decisions and being hesitant and absent when needed

Laissez-faire leadership reflects a complete absence of leadership behavior. Basically, leaders do nothing of what a situation asks for: they simply hide in plain sight. While it is important to learn behaviors that drive positive outcomes, it’s equally important to learn which behaviors drive negative outcomes.

Laissez-faire leadership outcomes

Our research shows that passive leadership behaviors drive negative outcomes by lowering:

- followers’ job satisfaction, satisfaction with the leader, and leader effectiveness (Judge & Piccolo, 2004; DeRue et al. 2011)

- followers’ organizational commitment (Jackson et al. 2013)

8. Leading change

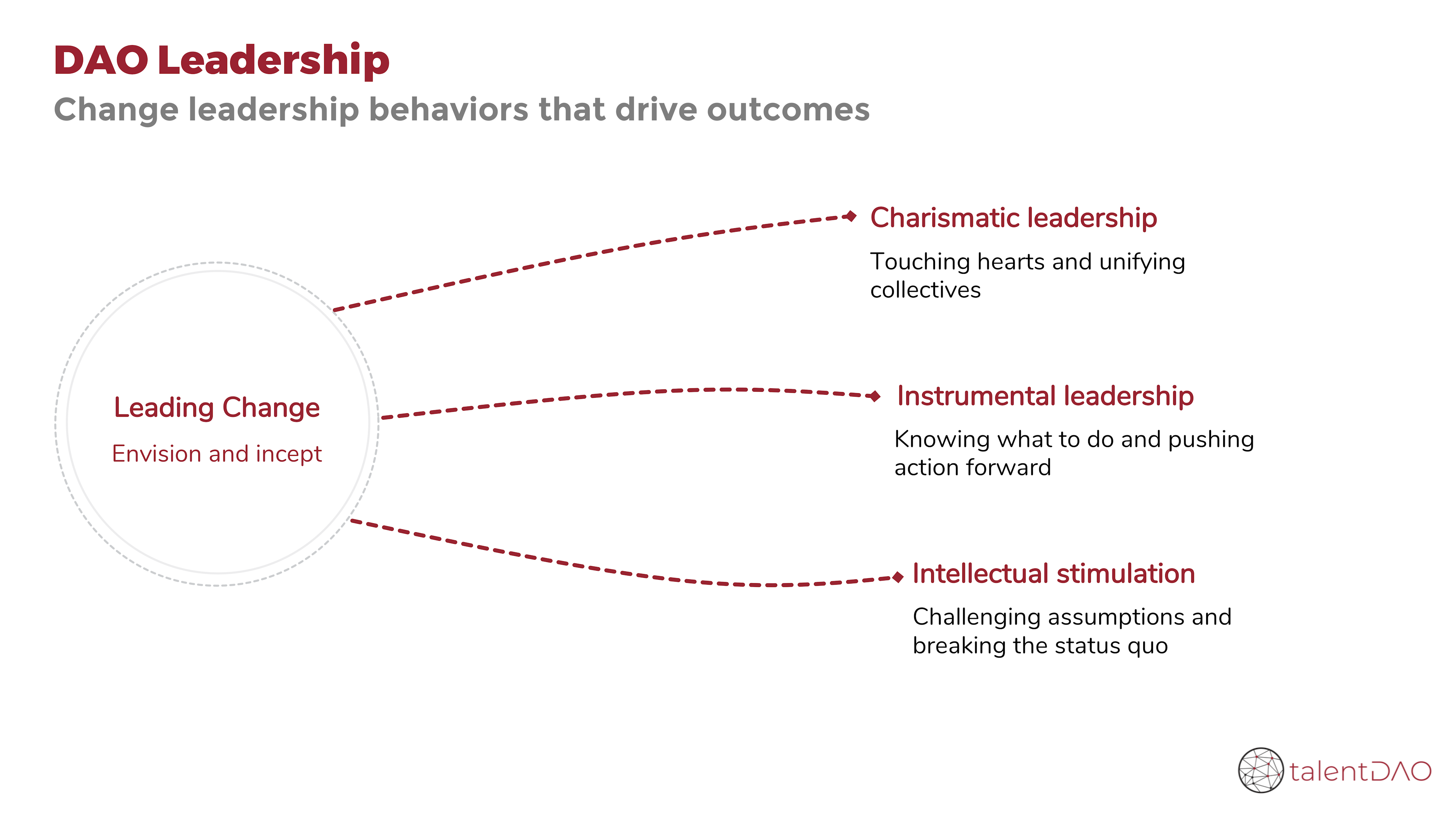

Leading change encompasses actions such as developing and communicating a vision for change, making strategic and tactical decisions, and encouraging innovative thinking and risk taking. Change leadership involves charismatic leadership, instrumental leadership, and intellectual stimulation.

Charismatic leadership

Charisma is not a miraculous ability, rather it is an effective way of saying things.

Antonakis et al. (2016) defined charismatic leadership as:

values-based, symbolic, and emotion-laden leader signaling

Charismatic leaders enhance followers by promoting social coordination through effective messaging. When convincing, people may give up their autonomy in favor of the leader's goals, such as working toward a specific cause. According to Antonakis (2016) charisma comprises three sets of behaviors:

- Justifying the mission by appealing to values that distinguish right from wrong.

- Communicating in symbolic ways to make the message clear and vivid, and also symbolizing and embodying the moral unity of the collective per se.

- Demonstrating conviction and passion for the mission displaying emotions.

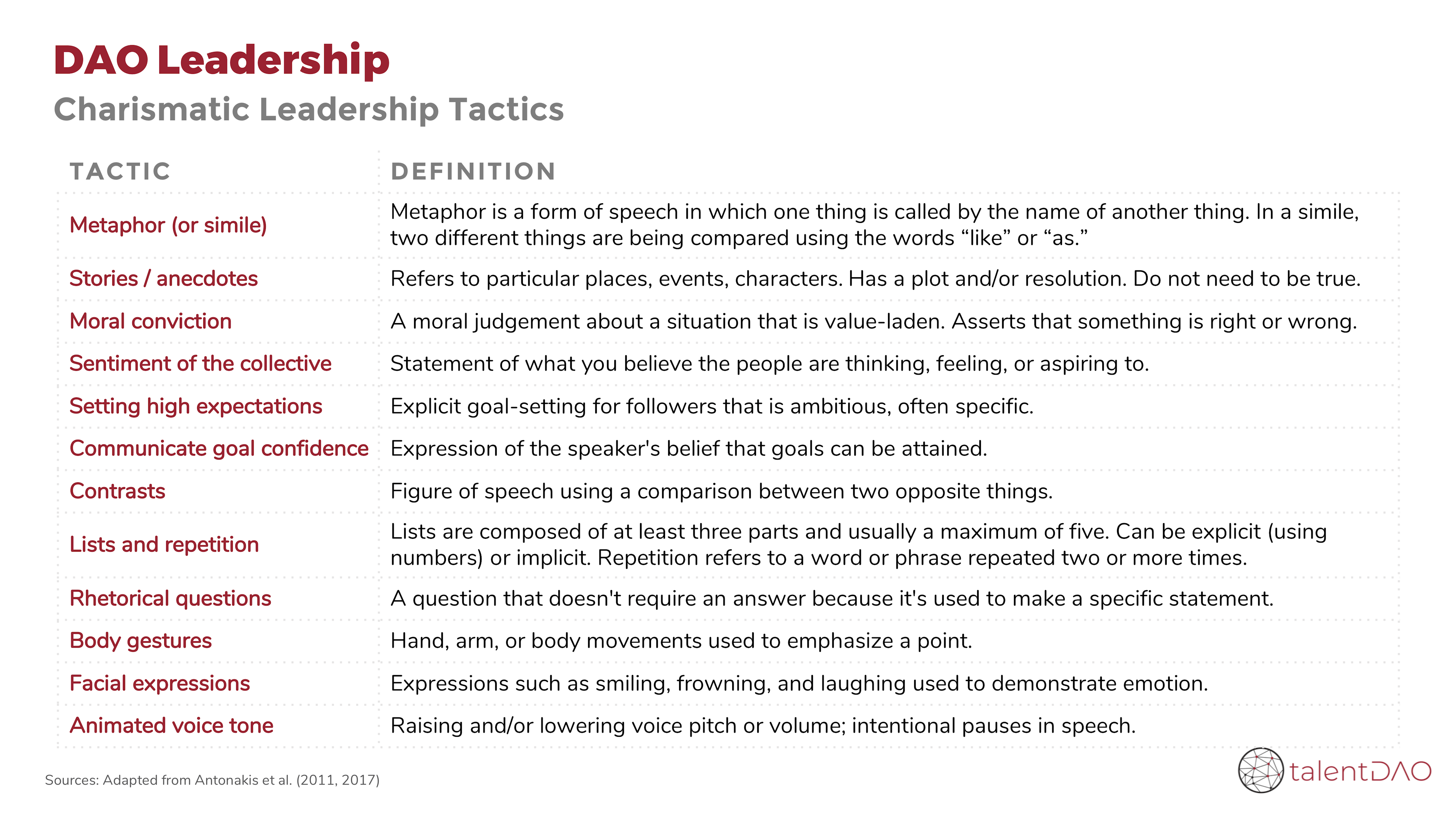

These behaviors translate practically in what Antonakis (2017) defined as Charismatic Leadership Tactics: six verbal and three non-verbal communication techniques.

Charismatic leadership outcomes

Our research shows that charismatic leadership behaviors correlate with:

- followers’ task performance and extra-role performance (Banks et al. 2017)

- followers’ perceptions of leaders’ prototypicality, competence, trustworthiness, and influencing ability (Ernst et al. 2021)

- followers’ identification with the leader and subsequent identification with the team and organization (Horstmaier et al. 2017; Koh et al. 2019);

- objective metrics of project success like costs, quality, time (Zhao et al. 2021)

Instrumental leadership

Antonakis and House (2014) defined instrumental leadership as:

the application of leader expert knowledge on monitoring the environment and performance, and the implementation of strategic and tactical solutions

Instrumental means just that: serving as a means to an end, that is, accomplishing the core functions of an organization such as meeting its objectives, adapting to its environment, and maintaining the stability of its system (Argyris, 1964).

According to Antonakis and House two dimensions make up the framework of instrumental leadership: strategic leadership and work facilitation. Each dimension comprises two sets of behaviors.

Strategic leadership

- Environmental monitoring: Leaders actions like scanning the internal and external organizational environments to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the organization and identify opportunities.

- Strategy formulation: Leaders actions focused on developing policies, goals, and objectives to support the strategic vision and mission.

Work facilitation

- Path-goal facilitation: Leaders behaviors targeted towards giving direction, support, and resources, removing obstacles for goal attainment and providing path-goal clarifications.

- Outcome monitoring: Leaders’ provision of performance-enhancing feedback useful for goal achievement.

Instrumental leadership outcomes

Our research shows that instrumental leadership behaviors correlate with:

- leader effectiveness and satisfaction with the leader above and beyond the effects of transformational and transactional leadership (Antonakis et al. 2014)

Intellectual stimulation

Judge & Piccolo (2004) defined intellectual stimulation as:

the degree to which the leader challenges assumptions, takes risks, and solicits creative ideas

Another facet of transformational leadership, intellectually stimulating people means engaging in unconventional behavior and not maintaining the status quo. This include:

- Encouraging innovative ways of thinking and doing things.

- Breaking away from existing routines and norms.

- Framing organizational change as an opportunity rather than a threat.

- Obtaining input from group members when solving change-related problems.

Intellectual stimulation outcomes

Our research shows that intellectual stimulation correlates with:

- team productivity (Burke et al. 2006), followers’ creative and innovative behaviors (Hughes et al. 2018), followers’ identification with the leader (Horstmaier et al. 2017)

9. Wrapping up: core DAO leadership

In this essay we synthesized the four categories of leadership behaviors that drive individual and team outcomes regardless of the organizational context. This evidence-base builds on decades of field research in the realm of organizational science, accounting for hundreds of thousands of participants in several organizational settings.

Sharing leadership means taking ownership of your behaviors, acting in ways that prompt the team processes that underlie team effectiveness. Since leaders’ behavior can have powerful impacts on collectives like teams, units, and organizations, our aim has been to give DAO members the means to an end, that is, evidence-based recommendations on which leadership behaviors to perform to drive DAO outcomes. Are you motivated to lead? Core DAO leadership equips you with the leadership skillset you can practice to drive progress, spur commitment, galvanize coordination, and contribute to make decentralized work become the future of work.

DAO Leadership NFT Editions

To reward our first research milestone and collect funds for our future research plan, we minted DAO Leadership NFT Editions. This tiered collection provides the following benefits (adding up from lower to upper tier):

- Legendary: NFT Art + talentDAO Genesis Club Eligibility

- Rare: NFT Art + Private educational workshop and advisory

- Common: NFT Art + Whitelist for all tiers of tDAO membership token + early access to future research via token gated Discord

The NFT Art represents an ecosystem being built on the shoulders of a sapient giant. People cooperate building megastructures and operating machines that recall the notable Italian inventor Leonardo Da Vinci. With the third eye wide open, the sapience, the giant supports us in building the new world of decentralized work.

Acknowledgements

This essay was written by Mr.Nobody in collaboration with Lisa Wocken. Cover illustration by Testasecca. We thank Kenneth Francis, ItamarGo, Lia Godoy, Saulthorin, and Riccardo Barbieri for their helpful feedback and support.

Disclaimer

All writers’ opinions in this article are their own and do not constitute financial advice in any way whatsoever. Nothing published here or on behalf of talentDAO constitute an investment recommendation, nor should any data or content published by talentDAO affiliates be relied upon for any investment activities.

About us

References

Antonakis, J., & House, R. J. (2014). Instrumental leadership: Measurement and extension of transformational–transactional leadership theory. The Leadership Quarterly.

Badura, K. L., Grijalva, E., Galvin, B. M., Owens, B. P., & Joseph, D. L. (2020). Motivation to lead: A meta-analysis and distal-proximal model of motivation and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology.

Banks, G. C., Engemann, K. N., Williams, C. E., Gooty, J., McCauley, K. D., & Medaugh, M. R. (2017). A meta-analytic review and future research agenda of charismatic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly.

Borgmann, L., Rowold, J., & Bormann, K. C. (2016). Integrating leadership research: A meta-analytical test of Yukl’s meta-categories of leadership. Personnel Review.

Brown, S. G., Hill, N. S., & Lorinkova, N. N. M. (2021). Leadership and virtual team performance: A meta-analytic investigation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology.

Burke, C. S., Stagl, K. C., Klein, C., Goodwin, G. F., Salas, E., & Halpin, S. M. (2006). What type of leadership behaviors are functional in teams? A meta-analysis. The Leadership Quarterly.

DeRue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., Wellman, N. E. D., & Humphrey, S. E. (2011). Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and meta‐analytic test of their relative validity. Personnel Psychology.

D’Innocenzo, L., Mathieu, J. E., & Kukenberger, M. R. (2014). A meta-analysis of different forms of shared leadership–team performance relations. Journal of Management.

Ernst, B. A., Banks, G. C., Loignon, A. C., Frear, K. A., Williams, C. E., Arciniega, L. M., ... & Subramanian, D. (2021). Virtual charismatic leadership and signaling theory: A prospective meta-analysis in five countries. The Leadership Quarterly.

Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., Van Dierendonck, D., & Liden, R. C. (2019). Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. The Leadership Quarterly.

Greer, L. L., de Jong, B. A., Schouten, M. E., & Dannals, J. E. (2018). Why and when hierarchy impacts team effectiveness: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Applied Psychology.

Harari, M. B., Williams, E. A., Castro, S. L., & Brant, K. K. (2021). Self‐leadership: A meta‐analysis of over two decades of research. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology.

Harms, P. D., Credé, M., Tynan, M., Leon, M., & Jeung, W. (2017). Leadership and stress: A meta-analytic review. The Leadership Quarterly.

Hiller, N. J., DeChurch, L. A., Murase, T., & Doty, D. (2011). Searching for outcomes of leadership: A 25-year review. Journal of Management.

Hoch, J. E., Bommer, W. H., Dulebohn, J. H., & Wu, D. (2018). Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. Journal of Management.

Hoch, J. E., & Kozlowski, S. W. (2014). Leading virtual teams: Hierarchical leadership, structural supports, and shared team leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology.

Horstmeier, C. A., Boer, D., Homan, A. C., & Voelpel, S. C. (2017). The differential effects of transformational leadership on multiple identifications at work: A meta‐analytic model. British Journal of Management.

Hughes, D. J., Lee, A., Tian, A. W., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2018). Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly.

Jackson, T. A., Meyer, J. P., & Wang, X. H. (2013). Leadership, commitment, and culture: A meta-analysis. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies.

Judge, T. A., & Piccolo, R. F. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology.

Karam, E. P., Hu, J., Davison, R. B., Juravich, M., Nahrgang, J. D., Humphrey, S. E., & Scott DeRue, D. (2019). Illuminating the ‘face’ of justice: A meta‐analytic examination of leadership and organizational justice. Journal of Management Studies.

Kim, M., Beehr, T. A., & Prewett, M. S. (2018). Employee responses to empowering leadership: A meta-analysis. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies.

Koeslag-Kreunen, M., Van den Bossche, P., Hoven, M., Van der Klink, M., & Gijselaers, W. (2018). When leadership powers team learning: A meta-analysis. Small Group Research.

Koh, D., Lee, K., & Joshi, K. (2019). Transformational leadership and creativity: A meta‐analytic review and identification of an integrated model. Journal of Organizational Behavior.

Knotts, K., Houghton, J. D., Pearce, C. L., Chen, H., Stewart, G. L., & Manz, C. C. (2021). Leading from the inside out: a meta-analysis of how, when, and why self-leadership affects individual outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology.

Krampitz, J., Seubert, C., Furtner, M., & Glaser, J. (2021). Self‐leadership: A meta‐analytic Review of Intervention Effects on Leaders’ Capacities. Journal of Leadership Studies.

Lee, A., Legood, A., Hughes, D., Tian, A. W., Newman, A., & Knight, C. (2020). Leadership, creativity and innovation: A meta-analytic review. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology.

Lee, A., Lyubovnikova, J., Tian, A. W., & Knight, C. (2020). Servant leadership: A meta‐analytic examination of incremental contribution, moderation, and mediation. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology.

Lee, A., Willis, S., & Tian, A. W. (2018). Empowering leadership: A meta‐analytic examination of incremental contribution, mediation, and moderation. Journal of Organizational Behavior.

Lord, R. G., Day, D. V., Zaccaro, S. J., Avolio, B. J., & Eagly, A. H. (2017). Leadership in Applied Psychology: Three Waves of Theory and Research. Journal of Applied Psychology.

Ng, T. W. (2017). Transformational leadership and performance outcomes: Analyses of multiple mediation pathways. The Leadership Quarterly.

Nicolaides, V. C., LaPort, K. A., Chen, T. R., Tomassetti, A. J., Weis, E. J., Zaccaro, S. J., & Cortina, J. M. (2014). The shared leadership of teams: A meta-analysis of proximal, distal, and moderating relationships. Leadership Quarterly.

Nohe, C., & Hertel, G. (2017). Transformational leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: A meta-analytic test of underlying mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology.

Peng, J., Li, M., Wang, Z., & Lin, Y. (2021). Transformational leadership and employees’ reactions to organizational change: Evidence from a meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science.

Scott-Young, C. M., Georgy, M., & Grisinger, A. (2019). Shared leadership in project teams: An integrative multilevel conceptual model and research agenda. International Journal of Project Management.

Sharma, P. N., & Kirkman, B. L. (2015). Leveraging leaders: A literature review and future lines of inquiry for empowering leadership research. Group & Organization Management.

Slemp, G. R., Kern, M. L., Patrick, K. J., & Ryan, R. M. (2018). Leader autonomy support in the workplace: A meta-analytic review. Motivation and Emotion.

Wang, D., Waldman, D. A., & Zhang, Z. (2014). A meta-analysis of shared leadership and team effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology.

Wang, G., Oh, I. S., Courtright, S. H., & Colbert, A. E. (2011). Transformational leadership and performance across criteria and levels: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of research. Group & Organization Management.

Wu, Q., Cormican, K., & Chen, G. (2020). A meta-analysis of shared leadership: Antecedents, consequences, and moderators. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies.

Zhao, N., Fan, D., & Chen, Y. (2021). Understanding the Impact of Transformational Leadership on Project Success: A Meta-Analysis Perspective. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience.